The following article was posted by Michael Eldridge on August 14, 2011 on the site, Working for the Yankee Dollar.

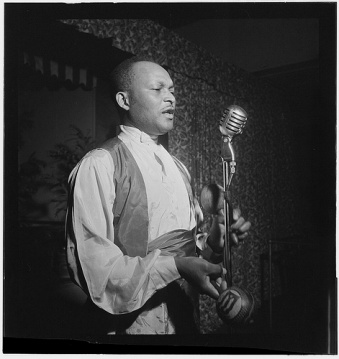

MacBeth the Great (Patrick MacDonald), probably at Renaissance Ballroom, July 1947 | From the William P. Gottlieb Collection of Jazz Photos, Library of Congress

I keep coming across bits of trivia I can’t believe I haven’t stumbled upon before. I already knew, thanks in part to Garl Jefferson, something of how calypso shared fans and venues with bebop in late 1940s Harlem. Turns out they even shared bills. Here’s a lovely anecdote from a famous piece previously unbeknownst to me, Paul Bacon’s “The High Priest of Bebop: The Inimitable Mr. Monk” (published originally in The Record Changer in 1949, it was reprinted in Rob Van der Bliek’s Thelonious Monk Reader):

There is, in Harlem, a monstrous barn of a dance-hall called the “Golden Gate”; quite a number of affairs are produced there every year, and the usual system is to have two alternating bands working–in the last few years the two bands have been one bop group and one Calypso band. (There are a couple of remarkable calypso bands in New York, playing a real powerhouse music which is closer to Harlem in 1928 than Trinidad in any year.) The occasion I’m thinking of took place there in 1947…Macbeth’s calypso contingent shared the stand with a bop sextet fronted by Monk; the boppers were second in line, so, after a long set by Macbeth, Monk’s band wandered desultorily to the stand.

Monk fussed with the piano, discovering that it was a pretty venerable instrument…Close examination showed him that the pedal post was shakily attached; he jiggled the whole piano apprehensively, then shrugged his shoulders and concentrated on some music left behind by Macbeth’s pianist.

A little later I became aware that Thelonious was doing something extraordinary…as I watched, mesmerised, I saw that he was yanking at the pedal post with all his might (first he kept up with the band by reaching up with his right hand to strike an occasional chord, but he had to apply himself to the attack on the post with both hands, and get his back into it, too). There was a slight crack, a ripping sound, and off came the whole works, to be flung aside as Monk calmly resumed playing. He never looked at it again, but when Macbeth’s man came back on the stand he stopped short, stunned. It was obvious that here was a new experience, something outside the ken of a rational man; for the rest of the evening he looked upon Thelonious with a new respect.

(Bacon, the designer of dozens of classic albums for Blue Note and Riverside in the 1950s and one of Monk’s early journalistic champions–jazz nerd and Down Beat writer/photograph Bill Gottlieb was another–was interviewed at length last year by Marc Myers for his blog JazzWax.)

Thelonious Monk at Minton’s Playhouse, ca. September 1947 | From the William P. Gottlieb Collection of Jazz Photos, Library of Congress

So Monk’s Caribbean connection wasn’t just second-hand. He grew up in San Juan Hill, an African-American neighborhood on Manhattan’s west side with a heavy West Indian presence. As Robin D. G. Kelley tells it in his magisterial biography of Monk, “With the music, cuisine, dialects, and manners of the Caribbean and the American South everywhere in [San Juan Hill], virtually every kid became a kind of cultural hybrid,” and on the radio, at block parties, and through his neighbors’ victrolas, Monk inevitably “absorbed Caribbean music” (23). His drummer Denzil Best, co-composer of the calypso-inflected “Bemsha Swing,” was the child of Bajan parents. (“Bimsha” is a phonetic approximation of “Bimshire,” one of Barbados’ nicknames.) His admirer and sometime student Randy Weston recorded “Fire Down There,” a/k/a “St. Thomas,” almost a year before Sonny Rollins did. (In fact, Weston once told Rhashidah McNeill that his waltz “Little Niles,” composed in honor of his young son, was inspired by a “swinging quadrille” played for him by MacBeth.) And while Monk’s go-to bassist and Weston’s childhood friend Ahmed Abdul-Malik, better known for his shared love (with Weston) of North African music, liked to tell people that his father was Sudanese, Robin Kelley claims that Abdul-Malik’s given name was Jonathan Timm and that both his parents were from St. Vincent. (The bassist covered “Don’t Stop the Carnival,” a road march claimed by Lord Invader but associated with the Duke of Iron and Virgin Islands carnival, on his 1961 album The Sounds of Ahmed Abdul-Malik–again, a year ahead of Rollins.) I’ve heard it rumored, moreover, that Abdul-Malik played for a time in MacBeth’s band.

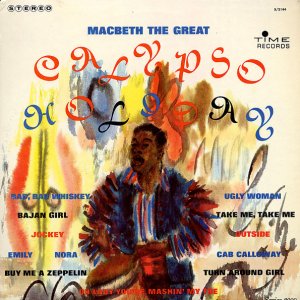

MacBeth the Great, “Calypso Holiday” (Time Records S2144, 1961)

As for MacBeth himself: born Patrick MacDonald in Trinidad, he made his first big mark as a performer singing with Gerald Clark’s band at the Village Vanguard in 1940. The stylistic contrast between MacBeth and one of the other featured singers, Sir Lancelot, was marked; as the Afro-American saw it, MacBeth “[stole] the show.” Short in stature, he nevertheless cut quite a figure: “Gayly dressed in red satin trousers, black loosely-belted tunic, casually draped black and green turban, the ends of which fall over his right shoulder, he sings the clever, clever words of the songs, shaking maracas.”[1] MacBeth recorded one tune, “I Love to Read Magazines,” with Clark for Varsity before the war, then more sides for Guild/Musicraft in 1945, Asch/Disc in 1946, Jade around 1949, and Monogram in the early 1950s. He participated in the famous “Calypso at Midnight” concert at New York’s Town Hall in 1946 and subsequently organized his own twelve-piece orchestra. (“Macbeth’s Calypso Band” also appeared on screen with Lord Invader in the “Pigmeat” Markham vehicle House-Rent Party that same year.) Besides playing in New York, where for many years he took part in Carnival balls in Harlem, Macbeth also performed up and down the East Coast. According to one account, his band was in such demand that it sometimes had to be “split into two groups in order to fulfill engagements which were scheduled on the same night.” After his death, the sides that MacBeth had done for Bob Shad‘s Jade label were collected on a 1964 album called Calypso Holiday, released by the legendary producer, jazz fan, and A & R man’s latest venture, Time Records. (Time was superseded by Mainstream, which was eventually acquired by Sony Legacy, who may be behind a recent digital reissue of MacBeth’s Jade sides–along with scores of other Mainstream titles.) MacBeth’s son Ralph MacDonald, an accomplished percussionist and sometime arranger for Harry Belafonte in the early 1960s, got his start in his father’s band.

Though it was Wilmoth Houdini who crowned himself “King” of the New York calypsonians, in July 1947 Houdini, the Duke of Iron, Lord Invader, and MacBeth the Great, along with “dark horse” the Count of Monte Cristo (the Duke’s brother), staged a monarchy competition at Harlem’s storied Renaissance Ballroom and Casino to determine “the undisputed right to the title of Calypso King.” (I suspect that’s where William Gottlieb’s “Portrait of Calypso” shots were captured.) I don’t know which of the rivals prevailed, or whether his victory was ever in fact disputed. But of course MacBeth’s kingly stature was implicit all along.

[1] “New Kind of Singing: Calypso has Four Parts.” Afro-American 22 June 1940: 13

For original article: “If chance will have me king, why, chance may crown me.” « Working for the Yankee Dollar.