“John Gray, master bibliographer of the Afro-Atlantic world has done it again. His powerful new work, Afro-Cuban Music: A Bibliographic Guide, covers the subject in all its facets, all its glory. I wandered happily through this wondrous text, learning, learning, learning. Gray makes you aware of what an amazing cultural machine black Cuba is, from the habanera to orisha rap and back again. A landmark publication in Black Studies.

-Robert Farris Thompson, Yale University, author of Aesthetic of the Cool: Afro-Atlantic Art and Music

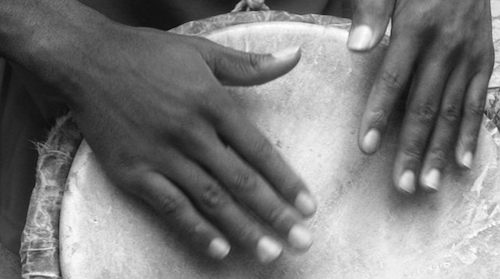

Despite its relatively small size Cuba has had an inordinately large musical influence both inside the Caribbean and abroad. From the “rhumba” craze of the 1920s and ’30s to mambo and cha-cha-cha in the 1950s and ’60s and the Buena Vista Social Club phenomenon of the late ’90s, Cuba has been central to popular music developments in Latin America, Europe, and the United States.

Unfortunately, no one has ever attempted to survey the extensive literature on the island’s music, in particular the vernacular contributions of its Afro-Cuban population. This unprecedented bibliographic guide, the third in ADP’s critically acclaimed Black Music Reference Series, attempts to do just that. Ranging from the 19th century to early 2009 Afro-Cuban Music offers almost 5000 annotated entries on the island’s various festival and Carnival traditions as well as each of its main musical families-Cancion Cubana, Danzon, Jazz, Son, Rumba, and Sacred Musics (Santeria, Palo, Abakua, and Arara)-along with more recent developments such as timba, rap and regueton. It also provides sections on Afro-Cuban musical instruments, the music’s influence abroad, and a biographical and critical component covering the lives and careers of some 800 individual artists and ensembles. Spanish-language sources are covered comprehensively, in particular dozens of locally published journals, along with a sizable cross-section of the international literature in English, French, German, and other European languages.

The work concludes with an extensive reference section offering lists of Sources Consulted, a guide to relevant Libraries and Archives, an appendix listing artists and individuals by idiom/occupation, and separate Author and Subject indexes.

An essential tool for students, scholars and librarians seeking a window into Afro-Cuban expressive culture-its music and dance, religion, language, literature, aesthetics, and more-both on the island and abroad.

The author is veteran bibliographer John Gray whose previous works include Blacks in Classical Music, African Music, Fire Music: a bibliography of the New Jazz, 1959-1990, From Vodou to Zouk, and, Jamaican Popular Music.

To order please visit the ADP website: www.african-diaspora-press.com<http://www.african-diaspora-press.com/>. The book is also available through most library wholesalers.

Reviews

Afro-Cuban Music: A Bibliographic Guide is an impressive accomplishment that will prove an invaluable resource for researchers. It is well-organized and offers comprehensive coverage of the available literature, particularly periodical sources which would otherwise be very difficult to find. Users will also appreciate the many annotations included for the details they provide on each work’s contents.

-Robin Moore, University of Texas at Austin, author of Nationalizing Blackness: Afrocubanismo and Artistic Revolution in Cuba, 1920-1940

Praise for the author’s previous works

-From Vodou to Zouk: “…will prove an indispensable, in-hand reference to current French Caribbean music scholarship”-Library Journal

“…represents a major update of available bibliographical guides…exceedingly pleasurable to recommend…”-Notes (Music Library Association)

-African Music: “…a truly outstanding achievement…likely to become the standard reference tool on African music for the next decade or so. Supersedes all previously available bibliographies in scope, the clear organization of its data, and of course, in its up-to-dateness”

-Folk Music Journal

Also Available

From Vodou to Zouk: a bibliographic guide to music of the French-speaking Caribbean and its diaspora (vol. 1)

Jamaican Popular Music, from Mento to Dancehall Reggae: a bibliographic guide (vol. 2)

Forthcoming (Fall 2012): Baila! A bibliographic guide to Afro-Latin dance musics, from Mambo to Salsa (Black Music Reference Series; vol. 4)

For original post: African-Diaspora Press/Afro-Cuban Music